Disease - Real-life applications

A Changing Threat

At one time the diseases that posed the greatest threat to human survival were infectious ones, such as the Black Death (actually a combination of bubonic and pneumonic plague), which killed about a third of Europe's population during the period from 1347 to 1351. Plagues or epidemics, in fact, are among the persistent themes in history, punctuating the fall of empires and the rise of others.

A plague that struck the eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire in the sixth century, for instance, brought an end to a plan by the great Justinian I to reconquer the Italian peninsula and restore Roman rule in western Europe. It also spelled the beginning of the end of Byzantine glory (though the empire hung on until 1453) and opened the way for the rise of Islam and Muslim influence over the Mediterranean. Thus, the course of history up to the present day, including the events of the European Middle Ages, the Crusades, and even the modern-day conflict between the West and Islamic terrorists, can be traced in part back to a plague in about A.D. 540.

Wherever people have gathered in large numbers, infectious diseases have arisen. Smallpox and chicken pox, cholera and malaria, diphtheria and scarlet fever, influenza and polio—these and many other diseases have threatened the very survival of whole populations, bringing about a collective death toll that dwarfs that of twentieth-century wars and genocide. Yet it was in the twentieth century—ironically, the era when humans discovered the capacity to kill themselves in truly frightening numbers through world wars, nuclear weaponry, and totalitarian social experiments—that the threat of infectious diseases began to recede.

Thanks to successful vaccination programs, many infectious diseases are largely a thing of the past. This is true even of smallpox, a scourge that effectively ended in 1978 thanks to a United Nations inoculation program, but which reemerged as a potential threat of biological terrorism

THE RISE OF INTRINSIC DISEASES.

Rather than infectious diseases, the much greater threat today is in the form of intrinsic diseases, or ones that are neither communicable nor contagious. The leading causes of death in the United States are as follows:

- Heart disease

- Cancer

- Stroke

- Chronic obstructive lung diseases (e.g., emphysema)

- Accidents (motor vehicle or other)

- Pneumonia and influenza

- Diabetes mellitus

- Suicide

- Kidney disease

- Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis

Note that the one item on the list that is not an intrinsic disease and is not disease-related at all: accidents. After that is the first extrinsic disease entry on the list, number 6, pneumonia and the closely related condition influenza. Number 8, of course, is not related to disease—at least not physical disease. The high incidence of suicide, with 11.1 such deaths per 100,000 population, probably reflects the fact that the United States is an industrialized, wealthy nation. Ironically, people who are eking out a living, struggling for survival, are far less likely to end it all voluntarily.

Also reflective of America's high level of development is the overwhelming preponderance of intrinsic, noninfectious diseases on the list. Unquestionably, the greatest threat to human health today takes the form of noninfectious diseases, such as heart disease, cancer, and diseases of the circulatory system. This is true only in the industrialized world, however: whereas only about 25% of all patients who visit doctors in the United States do so because of infectious diseases, more than two-thirds of all deaths worldwide are caused by infectious diseases, such as malaria.

Stress and Heart Disease

Stress, simply put, is a condition of mental or physical tension brought about by internal or external pressures. Many events can cause stress: something as simple as taking a test or driving through rush-hour traffic or as traumatic as the death of a loved one or contracting a serious illness. Stress may be short-lived, as when facing a particular deadline, or it may be the ongoing, crippling stress related to a job that is slowly killing the victim.

People who experience severe traumas, such as soldiers in combat, may experience a condition called post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This condition first came to public attention after World War I, a war that completely dwarfed all preceding conflicts in its intensity and brutality. Formerly bright-eyed, optimistic youths came home behaving like madmen or nervous wrecks, and soon the condition gained the nickname shell shock. (Actually, shell shock dated back more than 50 years, to what might be regarded as the first modern war in the West—the first "total war" involving relatively sophisticated weaponry and a fully engaged citizenry: America's Civil War, from which combatants returned home with a condition known as "soldier's heart.")

EFFECTS OF STRESS.

Whereas PTSD has a distinct psychological dimension, in many stress-related diseases there is not as obvious a link between mental states and bodily disorders. Nonetheless, it is clear that stress kills. Some of the physical signs of stress are a dry mouth and throat, headaches, indigestion, tremors, muscle tics, insomnia, and a tightness of the muscles in the shoulders, neck, and back. Emotional signs of stress include tension, anxiety, and depression. During stress, heart rate quickens, blood pressure increases, and the body releases the hormone adrenaline, which speeds up the body's metabolism. Stress may disrupt homeostasis, an internal bodily system of checks and balances, leading to a weakening of immunity.

Diseases and conditions associated with stress include adult-onset diabetes (see Noninfectious Diseases), ulcers, high blood pressure, asthma, migraine headaches, cancer, and even the common cold. The last, of course, is an infectious illness, but because stress impairs the immune system, it can leave a person highly susceptible to infection. Furthermore, medical researchers have determined that long-term stress causes the accumulation of fat, starch, calcium, and other substances in the linings of the blood vessels. This condition ultimately results in heart disease.

HEART DISEASES.

The human heart weighs just 10.5 oz. (300 g), but it contracts more than 100,000 times a day to drive blood through about 60,000 mi. (96,000 km) of vessels. An average heart will pump about 1,800 gal. (6,800 l) of blood each day. With exercise, that amount may increase as much as six times. In an average lifetime the heart will pump about 100 million gal. (380 million l) of blood. The heart is divided into four chambers: the two upper atria and the two lower ventricles. The wall that divides the right and left sides of the heart is the septum. Movement of blood between chambers and in and out of the heart is controlled by valves that allow transit in only one direction.

Given its importance to human life, it follows that heart disease is an extremely serious condition. Among the many illnesses that fall under the general heading of heart disease is congenital heart disease, a term for any defect in the heart that is present at birth. About one of every 100 infants is born with some sort of heart abnormality, the most common form being the atrial septal defect, in which an opening in the septum allows blood from the right and left atria to mix.

Coronary heart disease, also known as coronary artery disease, is the most common form of heart disease. A condition termed arteriosclerosis, in which there is a thickening of the artery walls, or a variety of arteriosclerosis known as atherosclerosis results when fatty material, such as cholesterol, accumulates on an artery wall. This forms plaque, which obstructs blood flow. When the obstruction occurs in one of the main arteries leading to the heart, the heart does not receive enough blood and oxygen, and its muscle cells begin to die.

Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease

A particularly frightening category of unexplained diseases includes those that attack and destroy the brain. Among them are two conditions named after German scientists: the psychiatrists Alfons Maria Jakob (1884-1931) and Hans Gerhard Creutzfeldt (1885-1964) and the neurologist Alois Alzheimer (1864-1915). Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease,

It appears that Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease ensues when a certain protein in the brain, known as prion protein, changes into an abnormal form. As to what causes that change, scientists remain in the dark. The disease attacks about one of a million people worldwide, and victims are typically about 50-75 years of age. During the 1990s something strange happened: the disease began affecting relatively large numbers of young people in the United Kingdom. A 1996 report of British medical experts, however, linked the surge in Creutzfeldt-Jakob cases to what might be considered a dietary condition: bovine spongiform encephalopathy, or mad cow disease, contracted from eating cattle with a form of prion disease. The only way to contract such a condition, however, is by eating the brain or spinal cord of an affected cow, something that could only happen in the case of hamburger or sausage, in which one does not always know what one is getting. The cows themselves got the disease from eating feed tainted with by-products of other cows, and as a result of the outbreak, Great Britain issued wide-ranging controls prohibiting the production of feed containing any materials from cows. (These particular feed-production practices were never common in the United States.)

Alzheimer's Disease

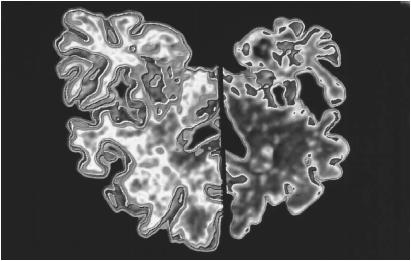

Whereas Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease is a little-known condition, Alzheimer's disease is all too familiar to the families of the more than four million sufferers in America today. Note the reference to the families rather than the victims themselves: one of the most devastating aspects of Alzheimer's disease is the patient's progressive loss of contact with reality, such that a patient in an advanced stage does not even know that he or she has the disease. A progressive brain disease that brings about mental deterioration, Alzheimer's disease is signaled by symptoms that include increasingly poor memory, personality changes, and a loss of concentration and judgment. Although most victims are older 65 years, Alzheimer's is not a normal result of aging. Up until the 1970s people assumed that physical and mental decline were normal and unavoidable features of old age and dismissed such cases of deterioration as "senility." Yet as early as 1906, Alzheimer himself discovered evidence that pointed in a different direction.

In that year Alzheimer was studying a 51-year-old woman whose personality and mental abilities were obviously deteriorating. She forgot things, became paranoid, acted strangely, and just over four years after he began working with her, she died. Following an autopsy, Alzheimer examined sections of her brain under a microscope and noted deposits of an unusual substance in her cerebral cortex—the outer, wrinkled layer of the brain, where many of the higher brain functions, such as memory, speech, and thought, originate. The substance Alzheimer saw under the microscope is now known to be a protein called beta-amyloid. About 75 years later scientists and physicians began to recognize a strong link between "senility" and the condition Alzheimer had identified. Since then, the public has become more aware of the disease, especially since Alzheimer's disease has stricken such well-known figures as the former president Ronald Reagan (1911-) and the actress Rita Hayworth (1918-1987).

THE IMPACT OF ALZHEIMER'S DISEASE.

A slight decline in short-term memory (as opposed to long-term memories of childhood and the like) is typical even in healthy elderly adults, but the memory loss seen in Alzheimer's disease is much more severe. As years pass, memory loss becomes greater, and personality and behavioral changes occur. Later symptoms include disorientation, confusion, speech impairment, restlessness, irritability, and the inability to care for oneself. Although victims may remain physically healthy for years, the progressive decline of their mental faculties is ultimately fatal: eventually, the brain loses the ability to control basic physical functions, such as swallowing. Persons with Alzheimer's disease typically live between five and ten years after diagnosis, although improvements in health care in recent years have enabled some victims to survive for 15 years or even longer.

Improvements in health care also may help explain the fact that the numbers of Alzheimer victims are growing. Medical discoveries of the twentieth century served to prolong life greatly, such that there are far more people alive today who are 65 years of age or older than there were in 1900. More accurate reporting no doubt plays a part as well. Whereas about 2.5 million cases were reported throughout the 1970s, by the end of the twentieth century there were some four million living Alzheimer victims, and by the mid-twenty-first century that number is expected to climb to the range of 13 million if physicians do not find a cure. Meanwhile, Alzheimer's causes the deaths of more than 100,000 American adults each year and costs $80-90 billion annually in health-care expenses.

UNDERSTANDING ALZHEIMER.

It is not a simple procedure to diagnose Alzheimer's disease, and despite all the medical progress since the time of Alois Alzheimer, the "best" method for determining whether someone has the condition is hardly a good one. The only possible physical procedure for definitively diagnosing Alzheimer's disease is to open the skull and remove a sample of brain tissue for microscopic examination. This is rarely done, of course, because brain surgery is far too drastic a procedure for simply obtaining a sample of tissue.

The immediate cause of Alzheimer's is the death of brain cells and a decrease in the connections between those cells that survive. But what causes that? Many scientists today believe that the presence of beta-amyloid protein is a cause in itself, while others maintain that the appearance of the protein is simply a response to some other, still unknown phenomenon. Researchers have found that a small percentage of Alzheimer cases apparently are induced by genetic mutations, but most cases result from unknown factors. Various risk factors have been identified, but they are not the same as causes; rather, a risk factor simply means that if a person has x, he or she is more likely to have y. Risk factors for Alzheimer's include exposure to toxins, head trauma (former president Reagan suffered a serious head injury before the onset of Alzheimer's disease), Down syndrome (a genetic disorder that causes mental retardation), age, and even gender (women are more likely than men to suffer from Alzheimer's disease).

Familial Alzheimer's disease, an inherited form, accounts for about 10% of cases. Approximately 100 families in the world are known to have rare genetic mutations that are linked with early onset of symptoms, and some of these families have an aggressive form of the disease in which symptoms appear before age 40. The remaining 90% of cases may be caused by various combinations of genetic and as yet undefined environmental factors.

WHERE TO LEARN MORE

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Web site). <http://www.cdc.gov/> .

DeSalle, Rob. Epidemic!: The World of Infectious Disease. New York: New Press, 1999.

Diseases, Disorders and Related Topics. Karolinska Institutet/Sweden (Web site). <http://www.mic.ki.se/Diseases/> .

Environmental Diseases from A to Z. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences/National Institutes of Health (Web site). <http://www.niehs.nih.gov/external/a2z/home.htm> .

Epidemiology. University of Minnesota, Crookston (Web site). <http://sunny.crk.umn.edu/courses/biolknut/1020/micro3> .

Ewald, Paul W. Plague Time: How Stealth Infections Cause Cancers, Heart Disease, and Other Deadly Ailments. New York: Free Press, 2000.

Garrett, Laurie. The Coming Plague: Newly Emerging Diseases in a World out of Balance. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1994.

Moore, Pete. Killer Germs: Rogue Diseases of the Twenty-First Century. London: Carlton Books, 2001.

National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (Web site). <http://www.nci.nih.gov/> .

Oncolink: University of Pennsylvania Cancer Center (Web site). <http://oncolink.upenn.edu/> .

Oldstone, Michael B. A. Viruses, Plagues, and History. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

"Plant and Animal Bacteria Diseases." University of Texas Institute for Cellular and Molecular Biology (Web site). <http://biotech.icmb.utexas.edu/pages/science/bacteria.html#disease> .

World Health Organization (Web site). <http://www.who.int/home-page/> .

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: