IMMUNITY AND IMMUNOLOGY

CONCEPT

Immunity is the condition of being able to resist a specific disease, particularly through means that prevent the growth and development of disease-carrying organisms or counteract their effects. It is regulated by the immune system, a network of organs, glands, and tissues that protects the body from foreign substances. Immunology is the study of the immune system, immunity, and immune responses. Progress in immunology over the past two centuries has made inoculation—the prevention of a disease by the introduction to the body, in small quantities, of the virus or other microorganism that causes the disease—widely accepted and practiced. Despite such progress, however, some diseases evade human efforts to counteract them through medicine or other forms of treatment. This is particularly the case with a disease in which the immune system shuts down entirely: a condition known as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, or AIDS.

HOW IT WORKS

IMMUNITY AND THE IMMUNE SYSTEM

The functioning of the immune system is considered in a separate essay, along with the means by which that system responds to foreign invasion. Also included in that essay is a discussion of allergies, which arise when the body responds to ordinary substances as though they were pathogens, or disease-carrying parasites. The body cannot know in advance what a pathogen will look like and how to fight it, so it creates millions and millions of different lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell. The principal types of lymphocyte are B cells and T cells. These cells recognize random antigens, or substances capable of requiring an immune response.

Certain researchers believe that while some B cells and T cells are directed toward fighting an infection, others remain in the bloodstream for months or even years, primed to respond to another invasion of the body. Such "memory" cells may be the basis for immunities that allow humans to survive such plagues as the Black Death of 1347-1351 (see Infectious Diseases). Other immunologists, however, maintain that trace amounts of a pathogen persist in the body and that their continued presence keeps the immune response strong over time.

IMMUNOLOGY

Immunology is the study of how the body responds to foreign substances and fights off infection and other disease-causing agents. Immunologists are concerned with the parts of the body that participate in this response, and this investigation takes them beyond looking merely at tissues and organs to studying specific types of cells or even molecules.

From ancient times, humans have recognized that some people survive epidemics, when the majority are dying. About 1,500 years ago in India, physicians even practiced a form of inoculation, as we discuss later. The modern science of immunology, however, had its beginnings only in 1798, when the English physician Edward Jenner (1749-1823) published a paper in which he maintained that people could be protected from the deadly disease smallpox by the prick of a needle dipped in the pus from a cowpox boil. (Cowpox is a related, less-lethal disease that, as its name suggests, primarily affects cattle.)

Later, the great French biologist and chemist Louis Pasteur (1822-1895) theorized that inoculation protects people against disease by exposing them to a version of the pathogen that is harmless enough not to kill them but sufficiently like the disease-causing organism that the immune system learns to fight it. Modern vaccines against such diseases as measles, polio, and chicken pox are based on this principle.

HUMORAL AND CELLULAR IMMUNITY.

In the late nineteenth century, a scientific debate raged between the German physician Paul Ehrlich (1854-1915) and the Russian zoologist Élie Metchnikoff (1845-1916) concerning the means by which the body protects against diseases. Ehrlich and his followers maintained that proteins in the blood, called antibodies, eliminate pathogens by sticking to them. This phenomenon and the theory surrounding it became known as humoral immunity. Metchnikoff and his students, on the other hand, had noted that certain white blood cells could swallow and digest foreign materials. This cellular immunity, they claimed, was the real way that the body fights infection. In fact, as modern immunologists have shown, both the humoral and cellular responses identified by Ehrlich and Metchnikoff, respectively, play a role in fighting disease.

REAL-LIFE APPLICATIONS

INOCULATION AND VACCINES

Inoculation is the prevention of a disease by the introduction to the body, in small quantities, of the virus or other microorganism that causes that particular ailment. It is a brilliant idea, yet one that seems to go against common sense. For that reason, it was a long time in coming: not until the time of Jenner, in about 1800, did the concept of inoculation become widely accepted in the West. Nonetheless, it had been applied more than 13 centuries earlier in India.

In the period between about 500 B.C. and A.D. 500, Hindu physicians made extraordinary strides in a number of areas, pioneering such techniques as plastic surgery and the use of tourniquets to stop bleeding. Most impressive of all was their method of treating smallpox, which remained one of the world's most deadly diseases until its eradication in the late 1970s. Indian physicians apparently took pus or scabs from the sores of a mildly infected patient and rubbed the material into a small cut made in the skin of a healthy person. The Indians' method was risky, and there was always a chance that the patient would become deathly ill, but the idea survived and gradually made its way west over the ensuing centuries.

SMALLPOX VACCINATION.

Smallpox, or variola, is carried by a virus that causes the victim's body to break out in erupting, pus-filled sores. Eventually, these sores dry up, leaving behind scars that may alter the appearance of the victim permanently, depending on the intensity of the disease. Such was the case with Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689-1762), a celebrated English writer and noblewoman. Known for her passionate relationships, romantic and otherwise, Lady Montagu had been scarred from youth by smallpox, and no doubt this experience gave her heightened concern for the victims of the disease. While she was in Turkey with her husband, Edward, an ambassador, she became aware of an inoculation method, probably based on the Hindu practice of many centuries before, used by local women. Lady Montagu arranged for her three-year-old son to be inoculated against smallpox in 1717, and after returning home, initiated smallpox inoculations in England.

Nonetheless, the problem remained that the inoculated person contracted a serious case of the disease and died, at least some of the time. More than 80 years later, in 1796, during a smallpox epidemic, Jenner decided to test a piece of folk wisdom to the effect that anyone who contracted cowpox became immune to human smallpox. He took cowpox fluid from the sores of a milkmaid named Sarah Nelmes and rubbed it into cuts on the arm of an eight-year-old boy, James Phipps, who promptly came down with a mild case of cowpox. Soon, however, James recovered, and six weeks later, when Jenner injected him with samples of the smallpox virus, the boy was unaffected.

Jenner, who published his findings after conducting additional tests, coined a new term for the type of inoculation he had used: vaccination, from the Latin word for cowpox, vaccinia. (The

RABIES AND POLIO INOCULATION.

The next advancement in the study of vaccines came almost 100 years after Jenner's discovery. In 1885 Pasteur saved the life of Joseph Meister, a nine-year-old boy who had been attacked by a rabid dog, by using a series of experimental rabies vaccinations. Pasteur's rabies vaccine, the first human vaccine created in a laboratory, was made from a version of the live virus that had been weakened by drying it over potash (sodium carbonate—burnt wood ashes).

Exactly 70 years later, the American microbiologist Jonas Salk (1914-1995) created a vaccine for poliomyelitis (more commonly known as polio), in which the skeletal muscles waste away and paralysis and often permanent disability and deformity ensue. Although polio had been known for ages, the first half of the twentieth century had seen an enormous epidemic in the United States.

The most famous victim of this scourge was the future president Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945), who contracted it while on vacation in 1921. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, polio remained a threat, especially to children; at the peak of the epidemic, in 1952, it killed some 3,000 Americans in one year, while 58,000 new cases were reported. At the same time, Salk was working on his vaccine, which finally was declared safe after massive testing on school-children. In 1961 an oral polio vaccine developed by the Polish-born American virologist Albert Sabin (1906-1993) was licensed in the United States. Whereas the Salk vaccine contained the killed versions of the three types of poliovirus that had been identified in the 1940s, the Sabin vaccine used weakened live poliovirus. Because it was taken by mouth, the Sabin vaccine proved more convenient and less expensive to administer than the Salk vaccine, and it soon overtook the latter in popularity. By the early 1990s health organizations reported that polio was close to extinction in the Western Hemisphere.

TRIUMPHS AND CONTINUING CHALLENGES.

Thanks to these and other vaccines, many life-threatening infectious diseases have been forced into retreat. In the United States, children starting kindergarten typically immunized against polio, diphtheria, tetanus, measles, and several other diseases. Other vaccinations are used only by people who are at risk of contracting a disease, are exposed to a disease, or are traveling to an area (usually in the Third World) where particular diseases are common. Such vaccinations include those for influenza, yellow fever, typhoid, cholera, and hepatitis A.

Internationally, 80% of the world's children had been inoculated as of 1990 for six of the primary infectious diseases: polio, whooping cough, measles, tetanus, diphtheria, and tuberculosis. Smallpox was no longer on the list, because efforts against it had proved overwhelmingly successful. (See Infectious Diseases for more on the threat, or nonthreat, of smallpox as a form of biological warfare.) Despite these successes, however, each year more than two million children who have not received any vaccinations die of infectious diseases. Even polio has continued to be a threat in some parts of the world: as many as 120,000 cases are reported around the world each year, most in developing regions. And as if the threat from age-old diseases were not enough, in the last quarter of the twentieth century a new killer entered the fray: AIDS.

AIDS

A viral disease that is almost invariably fatal, AIDS destroys the immune systems of its victims, leaving them vulnerable to a variety of illnesses. No cure has been found and no vaccine ever developed. The virus that causes AIDS has proved to be one of the most elusive pathogens in history, and so far the only effective way not to contract the disease is to avoid sharing bodily fluid with anyone who has it. This means not having sex without condoms (and, to be on the truly safe side, not having sex outside a committed, fully monogamous relationship) and not engaging in intravenous drug use. But there are some people who have contracted the AIDS virus through no actions or fault of their own: people who have received it in blood transfusions or, even worse, babies whose AIDS-infected mothers have passed the disease on to them.

Within two to four weeks of being infected with the virus that causes AIDS (HIV, human immunodeficiency virus), a patient will experience what at first seems like flu: high fever, headaches, sore throat, muscle and joint pains, nausea and vomiting, open ulcers in the mouth, swollen lymph nodes, and perhaps a rash. As the immune system begins to fight the invasion, some cells produce antibodies to neutralize the viruses that are floating free in the bloodstream. Killer T cells destroy many other cells infected with the AIDS virus, and the patient enters a phase of the disease in which no symptoms are evident.

Although at this point it seems as though the worst is over, in fact, the AIDS virus is at work on the immune system, quietly destroying the body's protection by infecting those T cells that would protect it. With an immune system that gradually becomes more and more unresponsive, the patient is made vulnerable to any number of infections. Normally, the body would be able to fight off these attacks with ease, but with the immune system itself no longer functioning properly, infectious diseases and cancers are free to take over. The result is a long period of increasing misery and suffering, sometimes accompanied by dementia or mental deterioration caused by the ravaging of the brain by disease. Whatever the course it takes, the end result of AIDS is always the same: not just death but a miserable, excruciatingly painful death.

BIRTH OF A KILLER.

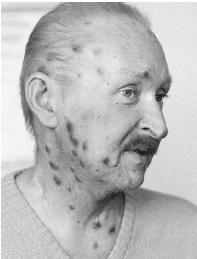

Believed to have originated in Africa, where the majority of AIDS cases still are found (see Infectious Diseases for statistics on AIDS), the disease first appeared in the United States in 1981. In that year two patients were diagnosed with an unusual form of pneumonia and with Kaposi's sarcoma, a type of cancer that previously had struck only people of Mediterranean origin aged 60 years and older. The appearance of that condition in younger persons of non-Mediterranean origin prompted an investigation by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Through the efforts of physicians both inside and outside the CDC, understanding of AIDS—the name and acronym appeared in 1982—gradually emerged. In 1983 scientists at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, as well as a separate team in the United States, identified the virus that causes AIDS, a pathogen that in 1986 was given the name human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Further research showed that HIV, a retrovirus (see Infectious Diseases for an explanation of retrovirus), is subdivided into two types: HIV-1 and HIV-2. In people who have HIV-2, AIDS seems to take longer to develop; however, neither form of HIV carries with it a guarantee that a person will contract the disease. At first it was believed that if someone were HIV-positive, meaning that the person had the virus, it was a virtual death sentence. Therefore in 1991, when the basketball superstar Earvin "Magic" Johnson (1959-) announced that he was HIV-positive, it was an extremely melancholy event. Fans and admirers all over the world assumed that Johnson shortly would contract AIDS and begin to wither away in the process of suffering an exceedingly panful, dehumanizing death.

The fact that Johnson was alive and healthy more than ten years after the diagnosis of his infection with HIV serves to indicate that there is a great deal of difference between being HIV-positive and having AIDS. It also says much about people's emerging understanding of the disease and the virus that causes it. So, too, does Johnson's experience as he attempted, twice, to make a return to the court after retiring in the wake of his HIV announcement. Before examining his experiences, let us look at the social climate engendered by this politically volatile immunodeficiency syndrome.

CHANGING VIEWS ON AIDS.

AIDS first was associated almost exclusively with the male homosexual community, which contracted the disease in large numbers. This had a great deal to do with the fact that male homosexuals were apt to have far more sexual partners than their heterosexual counterparts and because anal intercourse is more likely to involve bleeding and hence penetration of the skin shield that protects the body from infection. The association of AIDS with homosexuality led many who considered themselves part of the societal mainstream to dismiss AIDS as a "gay disease," and the fact that intravenous drug users also contracted the disease seemed only to confirm the prejudice that AIDS had nothing to do with heterosexual non-junkies. Some so-called Christian ministers even went so far as to assert, sometimes with no

Then, during the mid-1980s, AIDS began spreading throughout much of society: to heterosexuals, hemophiliacs (see Noninfectious Diseases) and others who received blood, and even babies. The fact that AIDS could be transferred through heterosexual intercourse proved that it was not just a disease of homosexuals. Nor were all homosexuals necessarily susceptible to it. In fact, the safest of all sexual groups was homosexual women, who often tended toward monogamy and whose form of sexual contact was least invasive.

As AIDS spread throughout society, so did paranoia. Rumors circulated that a person could catch the disease from a mosquito bite or from any contact with the bodily fluids of another person—not just semen or blood but even sweat or saliva. People with AIDS began to acquire the status lepers once had held (see Infectious Diseases). By the mid-1990s views had changed considerably, and society as a whole had a much more realistic view of AIDS. This came about to some extent because of increased education and awareness—and in no small part because of Johnson, who was by far the most widely knownand admired HIV-positive celebrity.

MAGIC COMES BACK.

After playing on the United States "Dream Team" that trounced all opponents at the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona, Spain, Johnson attempted a comeback with the Lakers the following year. Owing to fears on the part of many other players that they might contract AIDS by coming into close contact with him on the court, however, he decided again to retire. In December 1991 Johnson had established the Magic Johnson Foundation to promote AIDS awareness, and he devoted himself to this and other AIDS-related causes as well as to other ventures. Raising money for AIDS led him out onto the basketball court again in October 1995, when he and the American All Stars faced an Italian team in a benefit game, with an unsurprisingly lopsided score of 135-81.

Then, in February 1996, Johnson made his second attempted comeback with the Lakers. He ended up retiring again four months later, this time for good, but because he had chosen to and not because he had been forced to do so. Thanks in part to his AIDS education programs, in his second comeback Johnson discovered that players realized that they were not likely to catch the virus on the court. As the New Jersey Nets' player Jayson Williams told one reporter, "You've got a better chance of Ed McMahon knocking on your door with $1 million than you have of catching AIDS in a basketball game."

WHERE TO LEARN MORE

Aaseng, Nathan. Autoimmune Diseases. New York: Franklin Watts, 1995.

American Autoimmune Related Diseases Association, Inc. (AARDA) (Web site). <http://www.aarda.org/>.

Benjamini, Eli, and Sidney Leskowitz. Immunology: A Short Course. New York: Liss, 1988.

Clark, William R. At War Within: The Double-Edged Sword of Immunity. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Dwyer, John M. The Body at War: The Miracle of the Immune System. New York: New American Library, 1989.

Edelson, Edward. The Immune System. New York: Chelsea House, 1989.

How Your Immune System Works. How Stuff Works (Web site). <http://www.howstuffworks.com/immune-system.htm>.

"Infection and Immunity." University of Leicester Microbiology and Immunology (Web site). <http://www-micro.msb.le.ac.uk/MBChB/MBChB.html>.

"The Lymphatic System and Immunity." Estrella Mountain Community College (Web site). <http://gened.emc.maricopa.edu/bio/bio181/BIOBK/BioBookIMMUN.html>.

"Magic Johnson Retires Again, Saying It's on His Own Terms This Time." Jet , June 3, 1996, p. 46.

UNAids: The Joint UN Programme on HIV/AIDS (Web site). <http://www.unaids.org/>.

KEY TERMS

ALLERGY:

A change in bodily reactivity to an antigen as a result of a first exposure. Allergies bring about an exaggerated reaction to substances or physical states that normally would have little significant effect on a healthy person.

ANTIBODIES:

Proteins in the human immune system that help the body fight foreign invaders, especially pathogens and toxins.

ANTIGEN:

A substance capable of stimulating an immune response or reaction.

APC:

An antigen-presenting cell—a macrophage that has ingested a foreign cell and displays the antigen on its surface.

B CELL:

A type of white blood cell that gives rise to antibodies. Also known as a B lymphocyte.

EPIDEMIC:

Affecting or potentially affecting a large proportion of a population (adj.) or an epidemic disease (n.)

HUMORAL:

Of or relating to the antibodies secreted by B cells that circulate in bodily fluids.

IMMUNE SYSTEM:

A network of organs, glands, and tissues that protects the body from foreign substances.

IMMUNITY:

The condition of being able to resist a particular disease, particularly through means that prevent the growth and development or counteract the effects of pathogens.

IMMUNOLOGY:

The study of the immune system, immunity, and immune responses.

INOCULATION:

The prevention of adisease by the introduction to the body, in small quantities, of the virus or other microorganism that causes the disease.

LYMPHOCYTE:

A type of white bloodcell, varieties of which include B cells and Tcells, or B lymphocytes and T lymphocytes.

MACROPHAGE:

A type of phagocyticcell derived from monocytes.

MONOCYTE:

A type of white blood cell that phagocytizes (engulfs and digests) foreign microorganisms.

MONOGAMOUS:

Having only one mate.

PATHOGEN:

A disease-carrying parasite, usually a microorganism.

PHAGOCYTE:

A cell that engulfs and digests another cell.

T CELL:

A type of lymphocyte, also known as a T lymphocyte, that plays a key role in the immune response. T cells include cytotoxic T cells, which destroy virus-infected cells in the cell-mediated immune response; helper T cells, which are key participants in specific immune responses that bind to APCs, activating both the antibody and cell-mediated immune responses; and suppressor T cells, which deactivate T cells and B cells.

VACCINE:

A preparation containing microorganisms, usually either weakened or dead, which are administered as a means of increasing immunity to the disease caused by those microorganisms.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: