PREGNANCY AND BIRTH

CONCEPT

One of the greatest dramas in the world of living things is that which takes place in pregnancy and birth. Pregnancy forms a bond between mother and offspring that, in humans at least, lasts throughout life. Humans and many other animals are viviparous, meaning that offspring develop inside the mother's body and are delivered live. By contrast, birds and some other varieties of animal are oviparous, meaning that they deliver offspring in eggs that must develop further before hatching. In the modern world, human females experience birth in several ways—vaginal or cesarean, with anesthetics and without, at home or in a hospital—but just a few hundred years ago, there was little variety in an experience that was almost always painful and dangerous.

HOW IT WORKS

OVIPARITY, VIVIPARITY, AND OVOVIVIPARITY

The birth of live offspring is a reproductive feature shared by mammals, some fishes, and selected invertebrates, such as scorpions, as well as various reptiles and amphibians. Animals who give birth to live offspring are called viviparous, meaning "live birth." In contrast to viviparous animals, other animals—called oviparous, meaning "egg birth"—give birth to eggs that must develop before hatching. Finally, there are ovoviviparous animals, or ones that produce eggs but retain them inside the female body until hatching occurs, so that "live" offspring are born.

Oviparous animals may fertilize their eggs either externally or internally, though all animals that fertilize their eggs externally in nature are oviparous. (See Sexual Reproduction for more about internal and external fertilization.) In cases of internal fertilization, male animals somehow pass their sperm into the female: for example, male salamanders deposit a sperm packet, or spermatophore, onto the bottom of their breeding pond and then induce an egg-bearing (or gravid) female to walk over it. The female picks up the spermatophore and retains it inside her body, where the eggs become fertilized. These fertilized eggs later are laid and develop externally. Oviparous offspring undergoing development before birth obtain all their nourishment from the yolk and the protein-rich albumen, or "white," rather than from direct contact with the mother.

Ovoviviparity is common in a wide range of animals, including certain insects, fish, lizards, and snakes, but it is much less typical than oviparity. Ovoviviparous insects do not supply oxygen or nourishment to their developing eggs; they merely give them a safe brooding chamber for development. Nonetheless, species of ovoviviparous fish, lizards, and snakes appear to provide some nutrition and oxygen to their growing offspring. Because nutrition is provided in these instances, some zoologists consider them examples of true live birth, or viviparity.

VIVIPARITY.

Viviparity is the type of birth process that takes place in most mammals and many other species. Viviparous animals give birth to living young that have been nourished in close contact with their mothers' bodies. The offspring of both viviparous and oviparous animals develop from fertilized eggs, but the eggs of viviparous

All mammals, except for the platypus and the echidnas, are viviparous; only these two unusual mammals, called montremes, lay eggs. (See Speciation for more about mammal species.) Some snakes, such as the garter snake, are viviparous, as are certain lizards and even a few insects. Ocean perch, some sharks, and a few popular aquarium fish are also viviparous. Even certain plants, such as the mangrove and the tiger lily, are described as viviparous because they produce seeds that germinate, or sprout, before they become detached from the parent plant.

FROM ZYGOTE TO FETUS

The essays on Reproduction and Sexual Reproduction discuss the basics of the reproductive process through the point of fertilization. A fertilized egg is called a zygote, but once it begins to develop in the uterus or womb, it is known as an embryo and later, when it begins to assume the shape typical of its species, a fetus. In the uterus, the unborn offspring receives nutrients and oxygen during the period known as gestation, which extends from fertilization to birth. (In humans the gestation period is nine months.)

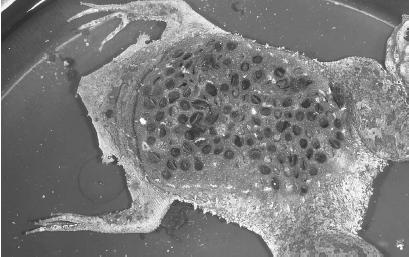

The zygote forms in one of the mother's fallopian tubes, the tubes that connect the ovaries with the uterus. It then travels to the uterus, where it becomes affixed to the uterine lining. Along the way, the zygote divides a number of times, such that by the time it reaches the uterus it consists of about 100 cells and is called an embryoblast. The exact day on which the embryoblast implants on the uterine wall varies, but it is usually about the sixth day after fertilization. By the end of the first week, a protective sac, known as the amniotic cavity, begins to form around the embryoblast.

EMBRYO AND FETUS.

Changes then begin to take place at a rapid rate. As each week passes, the embryo takes on more and more necessary and distinctive features, such as blood vessels in week 3, internal organs in week 5, and finger and thumb buds on the hands in week 7. Unfortunately, miscarriages are not uncommon in the early weeks of pregnancy. The mother's immune system (see Immune System) may react to cells from the embryo that it classifies as "foreign" and begin to attack those cells. The embryo may die and be expelled. The first three months of embryonic development are known as the first trimester, or the first three-month period of growth. At the end of the first trimester, the embryo is about 3 in. (7.5 cm) long and looks like a tiny version of an adult human. Thereafter, the growing organism is no longer an embryo, but a fetus. Fetal development continues through the second and third trimesters until the baby is ready for birth at the end of ninth months.

PREPARING FOR BIRTH

At the end of the gestation period, the mother's uterus begins to contract rhythmically, a process called labor. This is accompanied by the release of hormones, most notably oxytocin. From the time of fertilization, quantities of the hormone progesterone, which keeps the uterus from contracting, are high; but during the last weeks of gestation, maternal progesterone levels begin to drop, while levels of the female hormone estrogen rise. When progesterone levels drop to very low levels and estrogen levels are highest, the uterus begins to contract.

Meanwhile, as birth approaches, the brain's pituitary gland releases oxytocin, a hormone that stimulates uterine contractions and controls the production of milk in the mammary glands (a process called lactation). Synthetic oxytocin sometimes is given to women to induce labor. Scientists believe that the pressure of the fetus's head against the cervix, the opening of the uterus, ultimately initiates the secretion of oxytocin. As the fetus's head presses against the cervix, the uterus stretches and relays a message along nerves to the pituitary gland, which responds by releasing oxytocin. The more the uterus stretches, the more oxytocin is released.

LABOR AND DELIVERY.

Rhythmic contractions dilate the cervix, causing the fetus to move down the birth canal and to be expelled together with the placenta, which has supplied the developing fetus with nutrients from the mother during the gestation period. Before delivery, the placenta separates from the wall of the uterus. Since the placenta contains many blood vessels, its separation from the wall of the uterus causes bleeding. This bleeding is normal, assuming that it is not excessive. After the placenta separates from the uterine wall, it moves into the birth canal and is expelled from the vagina. The uterus continues to contract even after the placenta is delivered, and it is thought that these contractions serve to control bleeding.

After the baby is born, the umbilical cord that has attached the fetus to the placenta is clamped. The clamping cuts off the circulation of the cord, which eventually stops pulsing owing to the interruption of its blood supply. The baby now must breathe air through its own lungs, whereas before it has been breathing, fishlike, in the warm, wet environment of the mother's amniotic fluid. The process of labor described here in a very cursory fashion (it is actually much more complicated) can take from less than one hour to 48 hours, but typically the entire birth process takes about 16 hours.

REAL-LIFE APPLICATIONS

CHANGING VIEWS ON CHILDBIRTH

Before modern times, the realm of childbirth was a world exclusive to women, and few men ever entered the birth chamber. It was a place of excruciating pain and serious danger to the mother giving birth, so filled with blood and screaming that few men would have dared enter even if they had wanted to do so. Women had to give birth without anesthesia and any number of other amenities of modern medical care, including sophisticated diagnostic techniques and equipment, such as ultrasound, as well as antiseptic environments and surgical techniques, such as cesarean section.

In those days, birthing assistance was the work of midwives, women who lacked formal schooling in medicine (which was unavailable to most women in any case) but made up in experience for what they lacked in education. By about 1500, however, as medicine began to progress after many centuries of stagnation, male doctors increasingly forced midwives out of a job. In 1540 the European Guild of Surgeons declared that "no carpenter, smith, weaver, or woman shall practice surgery." A major turning point in the male takeover of birthing assistance duties came with the invention of the forceps, tong-like instruments that could be used for extracting a baby during difficult births. The inventor was the English obstetrician (a physician concerned with childbirth) Peter Chamberlen the Elder (1560-1631), and he and his descendants for a century closely guarded the design of the brilliant invention. Even the mothers on whom it was used never saw the instrument, and midwives were prohibited from using forceps to assist during childbirth.

OBSTETRICIANS TAKE OVER.

By the eighteenth century, however, Chamberlen's descendants had released their exclusive claim over the forceps, and use of the instrument spread to other medical professionals. This gave male obstetricians a great technological advantage over female midwives and further ensured the separation of the midwives from the medical profession. By 1750 numerous physicians and surgeons had gained the status of "man-mid-wives," and the growth of university courses on obstetrics established it as a distinct medical specialty. By the latter part of the 1700s, most women of the upper classes had come to rely on professionally trained doctors rather than midwives, yet in America, where doctors were scarcer than in Europe, the profession of midwife continued to flourish into the 1800s. Still, by the early twentieth century, childbirth had moved out of the home and into the hospital, and at mid-century it had become a completely medical process, attended by physicians and managed with medical equipment and procedures, such as fetal monitors, anesthesia, and surgical interventions.

THE REACTION IN THE LATE TWENTIETH CENTURY.

Many women of the late twentieth century found themselves dissatisfied with this clinical approach to childbirth. Some believed that the medical establishment had taken control of a natural biological process, and women who wanted more command over labor and delivery helped popularize new ideas on childbirth that sought to reduce or eliminate medical interventions. Today, some women choose to deliver with the help of a nurse-midwife, who, like her premodern counterparts, is trained to deliver babies but is not a doctor. There are women who even choose home birth, attended by a doctor or midwife or sometimes both. There are even brave souls who, in the face of increasing concern about the effect of anesthesia on the fetus, refuse artificial means of controlling pain and instead rely on breathing and relaxation techniques. For the first time in many years, the screams of women giving birth "naturally" once again filled the halls of hospital maternity wards and home birthing rooms.

MODERN CHILDBIRTH

The last few paragraphs represent an extreme reaction—a view not shared by many women, who have been more than happy to avail themselves of the benefits of childbirth in the modern world. Such benefits include an epidural, a type of anesthetic procedure that serves to alleviate the pain of parturition, or childbirth, while making it possible for the mother to remain conscious. Still, even for women who have no interest in giving birth at home or without the aid of drugs, much has changed in the world of childbirth. Women may choose a happy medium between the medical establishment and more traditional methods, for instance, by opting to consult with an obstetrician and a midwife.

Today, many obstetricians are women. This has had an incalculable effect on making childbirth psychologically easier for many women: though some are happy to retain a male obstetrician, many others find themselves much more comfortable being cared for by a physician who, in all likelihood, has given birth herself. The increasingly important role of the female obstetrician, along with other factors, serves to symbolize the fact that the world has progressed beyond the old false dilemma between medical care from a male or a female, between medicine and nature, between hospital and home.

A HOSPITAL AS HOME.

Hospital rooms, in fact, are starting to resemble rooms at home. Everywhere one looks in the modern maternity environment, there is evidence that much has changed, not only from the very old days, when male doctors were not involved in childbirth at all, but also from the more recent past, when males took over the process entirely. In a brilliant innovation, many hospitals have created a situation in which the woman gives birth in her own hospital room, which is outfitted with couches, cabinets, curtains, and rocking chairs to make it look like a home rather than a hospital. To emphasize the smooth transition between home life and the delivery room, fathers, once banished from the labor and delivery chambers, now are welcomed as partners in the birth process.

A father may even cut the umbilical cord, and he is certainly likely to be in the delivery room with a video camera, recording the event for posterity—yet another change from the past. Fathers are not the only ones filming in the delivery room. Today, cable television networks, such as the Learning Channel, provide programming that offers a frank view of the delivery process, complete with candid footage that sometimes can be as dramatic as it is revealing. The maternity ward, once a closed place, has increasingly become an open book.

SAVING AND IMPROVING LIVES

Many a mother and father alike can breathe a prayer (or at least a sigh) of thanks for all the innovations that today make birth much safer than it once was. Among them are a variety of techniques for embryo and fetal diagnosis, which help make parents aware of possible problems in the growing embryo. Ultrasound diagnosis, a technique similar to that applied on submarines for locating underwater structures, uses high-pitched sounds that cannot be heard by the human ear. These sounds are bounced off the embryo, and the echoes received are used to identify embryonic size.

By the eighteenth week of pregnancy, ultrasound technology can detect many structural abnormalities, such as spina bifida (various defects of the spine), hydrocephaly (water on the brain), anencephaly (no brain), heart and kidney defects, and harelip (in which the upper lip is divided into two or more parts). On a less dire and much more pleasant note, it can also give future parents an opportunity to gain their first glimpse of their child, and an experienced ultra-sound technician usually can tell them the baby's sex if they choose to learn it before the birth.

PRENATAL TESTING.

Chorionic villi sampling is the most sophisticated modern technique used to assess possible inherited genetic defects. This test typically is performed between the sixth and eighth week of embryonic development. During the test, a narrow tube is passed through the vagina or the abdomen, and a sample of the chorionic villi (small hairlike projections on the covering of the embryonic sac) is removed while the physician views the baby via ultrasound.

Chorionic villi are rich in both embryonic and maternal blood cells. By studying them, genetic counselors can determine whether the baby will have any of several defects, including Down syndrome (characterized by mental retardation, short stature, and a broadened face), cystic fibrosis (which affects the digestive and respiratory systems), and the blood diseases hemophilia, sickle cell anemia, and thalassemia. (Several of these disorders are discussed in different essays throughout this book; for instance, Down syndrome is examined in Mutation.) As with ultrasound, it also can show the baby's gender.

Another important form of prenatal (before the birth of the child) testing is amniocentesis, performed around week 16, in which amniotic fluid is drawn from the uterus by means of a needle inserted through the abdomen. Amniocentesis, too, can reveal the sex of the child, as well as a host of genetic disorders such as Tay-Sachs disease, cystic fibrosis, and Down syndrome. However, amniocentesis involves the risk of fetal loss as a result of disruption of the placenta. Chorionic villi sampling is even more risky, with an even higher possibility of fetal loss than amniocentesis, probably because it is conducted at an earlier stage.

In alpha-fetoprotein screening, which takes place somewhere between the 16th and 18th weeks, proteins from the amniotic sac and the fetal liver are taken as a means of screening for specific defects. Because of uncertainties involved in interpretation of the results, alpha-fetoprotein screening is not a common procedure.

CESAREAN SECTION.

Another extremely important technique that has saved the life of many babies and mothers is cesarean section. The normal position for a baby in delivery is head first; when a baby is in the breech position, with its bottom first, it poses grave dangers to both the mother and the child. Not only could the baby fail to emerge in time to begin breathing normally, thus running the risk of brain damage, but it also can become stuck, endangering the life of the mother. Today these dangers are overcome by such techniques as turning the baby and by cesarean section, an operation in which the baby is removed via surgery from the mother's abdomen. Cesarean sections may also be performed due to other complications, including fetal and/or maternal distress.

The term cesarean refers to the Roman emperor Julius Caesar (102-44 B.C.), who supposedly was delivered in this fashion. But the story of Caesar's birth is undoubtedly a legend: until the early modern era, cesarean sections were performed only to save a living baby after the mother had died in childbirth. The reason is that cesareans were likely to be fatal to the mother. Only in the late nineteenth century, by which time doctors had come to understand the importance of providing an antiseptic or germ-free environment, did cesarean sections become practical. Today the C-section, as it is called, has become a routine procedure—one that has saved literally hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of lives.

WHERE TO LEARN MORE

Assisted Reproduction Foundation (Web site). <http://www.reproduction.org/>.

Bainbridge, David. Making Babies: The Science of Pregnancy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Facts About Multiples (Web site). <http://mypage.direct.ca/c/csamson/multiples.html>.

Midwifery, Pregnancy, Birth and Breastfeeding (Web site). <http://www.moonlily.com/obc/>.

Pence, Gregory E. Who's Afraid of Human Cloning? Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 1998.

Pregnancy and Birth (Web site). <http://pregnancy.about.com/mbody.htm>.

Pregnancy and Reproduction Topics. Medline/National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health (Web site). <http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/pregnancyandreproduction.html>.

Rudy, Kathy. Beyond Pro-Life and Pro-Choice: Moral Diversity in the Abortion Debate. Boston: Beacon Press, 1996.

Vaughan, Christopher C. How Life Begins: The Science of Life in the Womb. New York: Times Books, 1996.

KEY TERMS

EMBRYO:

The stage of animal development in the uterus before the point at which the animal is considered a fetus. In humans this is equivalent to the first three months.

FALLOPIAN TUBES:

A set of trumpet-like tubes that carries a fertilized egg from the ovary to the uterus.

FERTILIZATION:

The process of cellular fusion that takes place in sexual reproduction. The nucleus of a male reproductive cell, or gamete, fuses with the nucleus of a female gamete to produce a zygote.

FETUS:

An unborn or unhatched vertebrate that has taken on the shape typical of its kind. An unborn human usually is called a fetus during the period from three months after fertilization to the time of birth.

GESTATION:

The time between fertilization and birth, during which the unborn offspring develops in the uterus.

HORMONE:

Molecules produced by living cells, which send signals to spots remote from their point of origin and induce specific effects on the activities of other cells.

OVARY:

Female reproductive organ that contains the eggs.

OVIPAROUS:

A term for an animal that gives birth to eggs that must develop before hatching. Compare with viviparous.

OVOVIVIPAROUS:

A term for an animal that produces eggs but retains them inside the body until hatching occurs, so that "live" offspring are born. Compare with oviparous and viviparous.

OVUM:

An egg cell.

UTERUS:

A reproductive organ, found in most female mammals, in which an embryo and, later, a fetus grows and develops.

VAGINA:

A passage from the uterus to the outside of the body.

VIVIPAROUS:

A term for an animal that gives birth to live offspring. Compare with oviparous.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: