SEXUAL REPRODUCTION

CONCEPT

Sexual reproduction is one of the two major ways, along with asexual reproduction, that plants and animals create offspring and thus propagate the species. Critical to sexual reproduction is the process of fertilization, whereby the male and female sex cells fuse, or bond. Fertilization may be of two types, either internal or external, and though humans normally fertilize by the first of those means, they may use the second, in the form of in vitro fertilization. Humans, of course, have by far the most complicated reproductive process, inasmuch as it is surrounded by a vast societal, interpersonal, and moral framework that is not a factor in animal reproduction. Part of that framework is the activity that precedes sexual reproduction: attraction, courtship, and so forth. Although no other animal's courtship rituals rival those of humans for sophistication, some of them are quite impressive in their complexity.

HOW IT WORKS

THE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM

The contrast between sexual and asexual reproduction is examined in Reproduction, an essay that also provides examples of plant reproduction through pollination. The present essay is concerned primarily with human sexual reproduction and secondarily with animal sexual reproduction. Some technical aspects of reproduction at the cellular level require consultation of processes explained in Genetics; here we confine our technical discussion to reproduction at the level of organs, fluids, and other bodily components. Reproduction is facilitated by the reproductive system, a group of organized structures that can be subdivided into male and female reproductive systems. During puberty, which typically occurs between the ages of 10 and 14 years, the reproductive systems of both sexes mature. This phase is marked in part by the release of eggs (female sex cells) in the female ovary and the formation of sperm (male sex cells) in the male testes. Reproduction can take place only when a sperm unites with an egg, a process called fertilization.

THE MALE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM.

The testes are the pair of male reproductive glands located in the scrotum, a skin-covered sac that hangs from the groin. Each testis produces sperm cells, while the testes as a whole secrete testosterone. Testosterone is a hormone—a type of molecule that sends signals to spots remote from its point of origin to induce specific effects on the activities of other cells. Testosterone is associated with masculinity, though females secrete it in much smaller quantities as well. In males, testosterone secretion is critical to the development of secondary sexual characteristics—those unique traits that mark a person as a male or female, though they do not occur in the sexual organs themselves. A deepened voice is an example of a male secondary sex characteristic evident at puberty.

Sperm cells produced in the testes move to the epididymis, a coiled tube at the base of the penis where they are stored and matured. During ejaculation, or the ejection of sperm from the penis during orgasm, sperm travel from the epididymis through a long tube called the vas deferens to the urethra. This single tube, which extends from the bladder to the tip of the penis, is also the means by which urine passes out of the body. Liquid secretions from various glands combine with sperm (itself a gooey substance that is barely liquid) to form the semen, or seminal fluid. Ejaculated semen may contain as many as 400 million sperm.

THE FEMALE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM

The female system is much more complicated than the male version and has a role in all stages of reproduction. Whereas the male system primarily delivers semen to the vagina, the female system plays a critical part from fertilization until long after the birth of offspring. It produces ova, or eggs, receives sperm from the penis, houses and provides nutrients to the developing zygote (fertilized egg) and later the embryo and fetus, gives birth to offspring, and feeds those offspring after birth.

The visible part of the female reproductive system, which, of course, is not even half of the entire picture, includes the opening of the vagina and the external genital organs, or vulva. The vagina, a muscular tube extending from the uterus to the outside of the body, is the receptacle for sperm ejaculated during sexual intercourse and also forms part of the birth canal that will be used later, when the offspring comes to term. The external genital organs, known collectively as the vulva, include the labia, folds of skin on both sides of the openings to the vagina and urethra; the clitoris, a small, sensitive organ that is comparable to the male penis inasmuch as it swells when stimulated; and the mons pubis, a mound of fatty tissue above the clitoris.

THE OVARIES AND MENSTRUATION.

Eggs are produced in the ovaries, oval-shaped organs in the groin that also generate sex hormones. At birth, a female's ovaries contain hundreds of thousands of undeveloped eggs, each surrounded by a group of cells to form a follicle, or sac; however, only about 360-480 follicles reach full maturity. During puberty the action of hormones causes several follicles to develop each month. Normally, just one follicle fully matures, rupturing and releasing an ovum through the ovary wall in a process called ovulation. The mature egg enters one of the paired fallopian tubes, where it may be fertilized by a sperm and move on to the uterus to develop into a fetus. The lining of the uterus, called the endometrium, prepares for pregnancy each month by thickening, but if fertilization does not take place, the endometrium is shed during menstruation.

FERTILIZATION

During sexual intercourse, a man releases approximately 300 million sperm into a woman's vagina, but only one of the sperm can fertilize the ovum. The successful sperm cell must enter the uterus, swim up the fallopian tube (a trumpet-shaped passageway between the ovary and the uterus) to meet the ovum, and then pass through a thick coating, known as the zona pellucida, that surrounds the egg. The head of the sperm cell contains enzymes (a type of protein that speeds up chemical reactions—see Enzymes) that break through the zona pellucida and allow the sperm to penetrate the egg. Once the head of the sperm is inside the egg, the tail falls off, and the outside of the egg thickens to prevent another sperm from entering. Many variables affect whether fertilization occurs after intercourse among humans. One factor is a woman's ovulatory, or menstrual, cycle. Human eggs can be fertilized for only a few days after ovulation, which typically occurs only once every 28 days. (To learn about what happens after fertilization, see Pregnancy and Birth.)

REAL-LIFE APPLICATIONS

EXTERNAL FERTILIZATION

Most land animals use some form of internal fertilization similar to that which we have described for humans. External fertilization, on the other hand, is more common among aquatic animals, who simply dump their sperm and eggs into the water and let currents mix the two male and female cells together. The sea urchin is a typical example: a male sea urchin releases several billion sperm into the water, and these sperm then swim toward eggs released in the same area. Fertilization occurs within seconds when sperm come into contact and fuse with eggs. As noted in Reproduction, external fertilization is essentially sexual reproduction without sexual intercourse. For humans the process of reproduction by external means may lack the intimacy of internal reproduction, but since 1978 a form of external fertilization has offered the opportunity of conceiving

IN VITRO FERTILIZATION.

This form of external fertilization is known as in vitro, or "in glass"—that is, in a glass test tube or petri dish. The term is contrasted with in vivo, meaning "in a living organism," or in utero, "in the uterus." During in vitro fertilization, eggs are removed surgically from a female's reproductive tract. They then can be fertilized in a test tube or petri dish by sperm taken from the woman's partner or another male. After the fertilized eggs have divided twice, indicating that the operation has "taken" and an embryo is starting to form, they are reintroduced to the female's body. If all goes well, the embryo and fetus eventually result in a normal birth.

In vitro fertilization has been performed successfully on a variety of domestic animals since the 1950s but on humans only since the late 1970s. Two English physicians, Patrick Steptoe (1913-1988) and Robert G. Edwards (1925-), developed a method for stimulating ovulation with hormone treatment and then retrieving the nearly mature eggs and placing them in a petri dish to mature. In their breakthrough 1978 operation, they added male sperm to the egg in the petri dish, where fertilization took place, and then implanted the eight-celled embryo in the mother's body. The result of this extraordinary operation was a healthy baby named Louise Brown.

A WORLD WITHOUT SEX?

The birth of Louise, whose twentieth birthday was celebrated in Britain with great fanfare, excited fears and controversy similar to those surrounding cloning (see Genetic Engineering). As with cloning, the fear was that the technology of in vitro fertilization would lead to the depersonalized manufacturing of human beings associated with some nightmarish future society, but this has not come to pass for several reasons. One is that in vitro fertilization is successful only about 15% of the time. Another, much more significant reason is that there are few women capable of producing a child through internal fertilization who would want to conceive without the intimacy of sexual intercourse.

There are exceptions, of course, in real life (two women in a same-sex relationship who want a child, for example) as well as in fiction. In the latter category, the character of Jenny Fields in the American novelist John Irving's World According to Garp—published, ironically, in the same year as the birth of Louise Brown—would undoubtedly have conceived a child by in vitro means if those means had been available to her. As it was, Jenny, who conceived the book's title character during World War II, manages to do so by having intercourse purely for the purpose of producing offspring. She does this by choosing a wounded, brain-damaged airman who will never remember having had sex with her and who dies shortly thereafter.

COURTSHIP

There is something far greater than mere biochemistry involved in sexual reproduction, which is why humans enjoy the intimacy of producing a baby. This is also why courtship and mating rituals are a significant part of human life, providing a means by which a male and female join as partners. Such is true even in modern America and the West in general, where the aftermath of the 1960s sexual revolution has left behind a world largely stripped of its former mystery. For better or worse, sex before marriage is a common part of life today in a way that it was not before the 1960s, with the advent of birth control and "free love," and today there is little stigma attached to the conception of a child outside wedlock. That much has changed—and changed dramatically—but humans still practice courtship.

Males still have to prove to females that they are suitable mates, usually by displaying their physical prowess or some other attribute associated with masculinity. Females still do most of the choosing, and despite all the changes in views toward male and female roles, the ideas of basic male and female differences seem to be hardwired into the minds of most people. This is particularly so of people who are heterosexual and especially those who either have children or intend to have them. Such attitudes are not surprising, since humans, while being something more than animals, are still animals as well.

ANIMAL COURTSHIP.

Among animals, courtship is a complex set of behaviors that leads to mating. Courtship behavior communicates to each potential mate that the other is not a threat and serves to reveal to each that the species, gender, and physical condition of the other are suitable for mating. During courtship,

CHOOSING A MATE.

Usually, the females do the choosing. In some species of birds, males display themselves in a small communal area called a lek, where females select a mate from the parading males. Across the animal kingdom, males generally compete with one another for mates, either by fighting or by ritualized displays, and females pick the best quality of

Genetic fitness, or the ability to survive—and to advance the survival of the species—is another important factor in mate selection. This is a large part of the reason why males may fight each other for a female—to show her that they are the most fit. Of course, the female animal does not know that she is choosing on this basis, but she is, and she is likely to select a partner with a striking appearance, capable of energetic displays—both of which are signs of good health.

SECONDARY SEX CHARACTERISTICS, EVOLUTION, AND THE MODEL OF AN IDEAL MATE

Humans, too, have deeply ingrained ideas regarding what makes an attractive potential mate, though to some extent, those ideas are cultural. Most societies regard a muscular male as attractive, for obvious evolutionary reasons: a physically fit male can provide for his mate and offspring, both by acquiring food and other resources and by protecting the nest. On the other hand, the modern American ideal of feminine beauty is more removed from nature. For one thing, this image of an attractive female is a thin body but large breasts—two things that seldom go together in nature but which are possible in the modern world through breast implantation surgery. That is, the achievement of such an ideal is available to a woman with a naturally thin body who also possesses the financial resources (and, of course, the desire) to undergo such surgery.

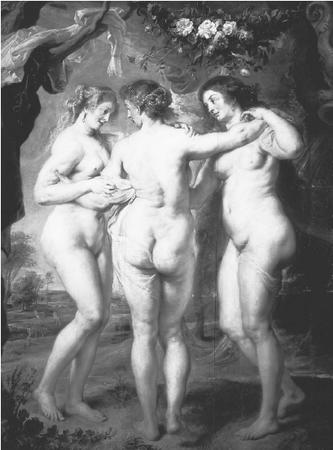

A woman naturally gifted with large breasts is apt also to have large buttocks, hips, and thighs, and while some men may find such anatomical features (particularly the first) desirable, this more natural version of the female body is not the image usually promoted in advertising or other media. Therefore, if a woman with a full figure wishes to meet societal expectations regarding beauty, she must endure something much more strenuous than a mere operation—a strict low-fat diet and a great deal of exercise. Given these often unnatural expectations from society, it is no wonder that a great many women express frustration with their attempts to conform to them, nor is it any wonder that many women in the modern world simply stop trying to conform. In any case, the American ideal of a thin female is far from universal, in terms of either place or time. Many traditional cultures favor a more amply formed female body, as did Western civilization in the past—a fact exemplified by the paintings of seventeenth-century artists, such as Peter Paul Rubens, famous for his fleshy female subjects. This is an ideal much closer to nature, since our evolutionary lineage has tended to favor women with large hips who are capable of bearing many children.

EVOLUTION AND THE SENSITIVE MAN.

As with much else about sexual reproduction and the courtship rituals associated with it, the idea of beauty—itself an expression of secondary sex characteristics—is much simpler for men. As we noted earlier, physical fitness in men almost always is regarded as attractive, but women often value men for other traits, most notably intelligence and sense of humor. Whereas many men place an emphasis on physical appearance in choosing a mate, women's expectations are much more complex and they are also likely to be much more forgiving toward members of the male population who do not look like Tom Cruise or some other Hollywood image of attractiveness.

In defense of modern men, many have complained that modern women do not always want what they say they want. For example, from the early 1970s onward, it often was said in public discussions of sexuality on TV or in magazines that women wanted men to be more sensitive. That is, they wanted men who were more verbal and given to talking about their feelings and who were more aware of the woman and her needs. It is not surprising that men were failing to meet these expectations, since the idea of the "strong, silent type" is a masculine ideal in many cultures. Furthermore, not only civilization but also evolution has tended to favor men who are given more to actions than to words—men who can make war, either on the battlefield or in the business world.

Such aggressive characteristics are all well and good among animals or in a human society just struggling to survive. But in the modern West, where most material needs are easily met, women have sought and expressed a desire for something more from men. Such was the situation that emerged in the wake of the sexual revolution, when people became more open not only about sex itself but about their feelings as well. Although the sexual revolution yielded a number of negative effects, including the loss of mystery associated with sex and an increase in out-of-wedlock pregnancies and cases of sexually transmitted disease, it also made it possible for people to be frank in a way that they had never been before. One outgrowth of this was the revelation, in many women's magazines, that women were no longer satisfied or impressed with strong, silent men.

During the 1970s the model of the sensitive man emerged, and for the first time it became possible for men to talk about their feelings. And they did, in books, in movies such as those of Woody Allen, and in therapist-led encounter groups or men's groups. Gradually, however, a surprising fact emerged: women did not want men to be too sensitive and certainly not too nonmasculine. They wanted a man who would talk about his feelings but not a man who wore his heart on his sleeve. They wanted to be treated as equals in the workplace, but if there was a strange noise in the house at night, they wanted the man to go see what it was. They wanted a man who would respect them—but not a man who was so polite and predictable that he possessed no air of mystery.

All of this reveals a great deal about humans and sexual reproduction. First of all, mating, or the interaction between males and females, is about far more than reproduction or even sex. It is an interaction that involves the whole person. Second, human sexuality is surrounded by webs of psychological, social, and spiritual complexity that make it a phenomenon quite different from animal sexuality, which tends to be about little more than procreation. And, third, for all the progress humans have made, and for all the levels of civilization that separate us from our evolutionary roots, there is still something in human sexuality that responds to very basic ideas about sex, the sexes, and the need to propagate the species through mating and reproduction.

WHERE TO LEARN MORE

Avraham, Regina. The Reproductive System. Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 2001.

Cool Nurse (Web site). <http://www.coolnurse.com/>.

Francoeur, Robert T. Taking Sides: Clashing Views on Controversial Issues in Human Sexuality. Guilford, CT: Dushkin Publishing Group/Brown and Benchmark, 1996.

"How Human Reproduction Works." How Stuff Works (Web site). <http://www.howstuffworks.com/human-reproduction.htm>.

Kimball, Jim. "Sexual Reproduction in Humans." Kim ball's Biology Pages (Web site). <http://www.ultranet.com/~jkimball/BiologyPages/S/Sexual_Reproduction.html>.

Parker, Steve. The Reproductive System. Austin, TX: Raintree Steck-Vaughn, 1997.

"Puberty Guide in Adolescents." Keep Kids Healthy (Website). <http://www.keepkidshealthy.com/adolescent/puberty.html>.

"Puberty Information for Boys and Girls." American Academy of Pediatrics (Web site). <http://www.aap.org/family/puberty.htm>.

Whitfield, Philip. The Human Body Explained: A Guide to Understanding the Incredible Living Machine. New York: Henry Holt, 1995.

Winikoff, Beverly, and Suzanne Wymelenberg. The Whole Truth About Contraception: A Guide to Safe and Effective Choices. Washington, DC: Joseph Henry Press, 1997.

KEY TERMS

CHROMOSOME:

A DNA-containing body, located in the cells of most living things, that holds most of the organism's genes.

DIPLOID:

A term for a cell that has the basic number of doubled chromosomes.

EGG CELL:

A female gamete.

EMBRYO:

The stage of animal development in the uterus before the animal is considered a fetus. In humans this is equivalent to the first three months.

FALLOPIAN TUBES:

A set of trumpet-like tubes that carries a fertilized egg from the ovary to the uterus.

FAPS:

Fixed-action patterns of behavior, or strong responses on the part of ananimal to particular stimuli. FAP is virtually synonymous with instinct.

FERTILIZATION:

The process of cellular fusion that takes place in sexual reproduction. The nucleus of a male reproductive cell, or gamete, fuses with the nucleus of an female gamete to produce a zygote.

FETUS:

An unborn or unhatched vertebrate that has taken on the shape typical of its kind. An unborn human usually is called a fetus during the period from three months after fertilization to the time of birth.

GAMETE:

A reproductive cell—that is, a mature male or female germ cell that possesses a haploid set of chromosomes and is prepared to form a new diploid by undergoing fusion with a haploid gamete of the opposite sex. Sperm and egg cells are, respectively, male and female gametes.

GENITALIA:

The sex organs, which include the male penis and the female vagina.

GESTATION:

The period between fertilization and birth during which the unborn offspring develops in the uterus.

HAPLOID:

A term for a cell that has half the number of chromosomes that appear in a diploid or somatic cell.

HORMONE:

Molecules produced by living cells, which send signals to spots remote from their point of origin and induce specific effects on the activities of other cells.

MENSTRUATION:

Sloughing off of the lining of the uterus, which occurs monthly in non pregnant females who have not reached menopause (the point at which menstrual cycles cease) and which is manifested as a discharge of blood.

OVARY:

Female reproductive organ that contains the eggs.

OVUM:

An egg cell.

PUBERTY:

A stage in the maturation of humans and higher primates where in the person first becomes capable of sexual reproduction. It is marked by the development of secondary sex characteristics, the maturation of the genital organs, and the beginning of menstruation in females. Puberty typically takes place somewhere between the ages of about 10 and 14 years.

SECONDARY SEX CHARACTERISTICS:

Those unique traits that mark an individual as a male or female but which are not manifested in the sexual organs themselves. Facial hair and a deep voice in males or breast development as well as hip and buttocks development in females areexamples.

SEXUAL REPRODUCTION:

One of the two major varieties of reproduction, along with asexual reproduction. In contrast to asexual reproduction, which involves a single organism, sexual reproduction involves two. Sexual reproduction occurs when male and female gametes undergo fusion, a process known as fertilization, and produce cells that are genetically different from those of eitherparent.

SPERM CELL:

A male gamete.

TESTES:

The pair of male reproductive glands located in the scrotum, a skin-covered sac that hangs from the groin.

UTERUS:

A reproductive organ, found in most female mammals, in which an embryo and later a fetus grow and develop.

VAGINA:

A passage from the uterus to the outside of the body.

ZYGOTE:

A diploid cell formed by the fusion of two gametes.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: