Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's is a brain disease in which damaged and dying brain cells cause devastating mental deterioration over a period of time. Often confused with senility (mental and physical deterioration associated with old age), its symptoms include increasingly poor memory, personality changes, and loss of concentration and judgment. The disease affects approximately four million people in the United States. Although most victims are over age 65, Alzheimer's disease is not a normal result of aging. Medication can relieve some symptoms in the early stages of the disease, but there is no effective treatment or cure. Its exact cause remains unknown.

History

Alzheimer's disease is named after German neurologist Alois Alzheimer (1864–1915), who was the first to describe it. In 1906, he studied a 51-year-old woman whose personality and mental abilities were obviously deteriorating: she forgot things, became paranoid, and acted strangely. After the woman's death, Alzheimer examined her brain at autopsy (examination of a dead body to find the cause of death or investigate the damage produced by disease) and noted an unusual thickening and tangling of the organ's nerve fibers. He also found that the cell body and nucleus of nerve cells had disappeared. Alzheimer noted that these changes indicated some new, unidentified illness. More than seven decades would pass before researchers again turned their attention to this puzzling, destructive disease.

Words to Know

Beta amyloid protein: A protein that accumulates in the brains of Alzheimer's disease victims.

Neocortex: The deeply folded outer layer of the cerebrum, controlling higher brain functions such as memory, speech, and thought.

Neurofibrillary tangle: An abnormal collection of bunched and twisted fibers found in dying neurons.

Proteins: Large molecules that are essential to the structure and functioning of all living cells.

Senility: Mental and physical deterioration of old age once considered a normal process of aging.

A progressive disorder

Alzheimer's is a tragic disease that slowly destroys its victim's brains, robbing them of the thoughts and memories that make them unique human beings. Patients with Alzheimer's typically progress through a series of stages that begin with relatively minor memory loss of recent events. Gradually, loss of memory is accompanied by forgetfulness, inattention to personal hygiene, impaired judgment, and loss of concentration. Later symptoms include confusion, restlessness, irritability, and disorientation. These conditions worsen until patients are no longer able to read, write, speak, recognize loved ones, or take care of themselves. Survival after onset of symptoms is usually five to ten years but can be as long as twenty years. Persons with Alzheimer's are especially vulnerable to infection (particularly pneumonia), which is the usual cause of death.

Changes in the brain

A healthy brain is composed of billions of nerve cells (neurons), each consisting of a cell body, dendrites, and an axon. Dendrites and axons together are called nerve fibers and are extensions of the cell body. Nerve messages enter a neuron by way of the dendrites and leave by way of the axon. Neurons are separated from one another by narrow gaps called synapses. Messages traveling from one neuron to another are carried across these narrow gaps by chemicals called neurotransmitters. This highly organized system allows the brain to recognize stimuli and respond in an appropriate manner.

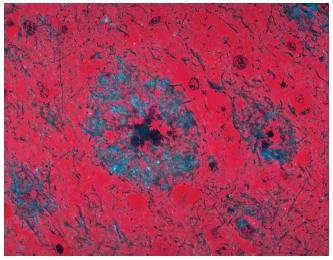

In Alzheimer patients, this orderly system becomes damaged to such a degree that it no longer works. The brains of Alzheimer's patients examined at autopsy show two hallmark features: (1) a mass of fibrous structures called neurofibrillary tangles and (2) plaques consisting of a core of abnormal proteins embedded in a cluster of dying nerve endings and dendrites. Lowered levels of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (pronounced uh-seh-tuhl-KOH-leen) are also observed. The brains of Alzheimer's disease victims appear shrunken, particularly in large parts of the neocortex, the outer layer of gray matter responsible for higher brain functions such as thought and memory. Much of the shrinkage of the brain is due to loss of brain cells and decreased numbers of connections, or synapses, between them.

Diagnosing Alzheimer's disease. There is no simple procedure, such as a blood test, to diagnose Alzheimer's. A definitive diagnosis can only be made by examining brain tissue after death. Diagnosis in a live patient is based on medical history, physical examination, laboratory tests to rule out other possible causes of symptoms, and neurological exams to test mental performance. Using these methods, physicians can accurately diagnose 90 percent or more of cases.

Risk factors for Alzheimer's disease. The specific cause of Alzheimer's disease remains unknown, although risk factors include advanced age, trauma such as head injury, and gene mutations. (Genes are the units of inheritance, and mutations are permanent changes to them.) When the disorder appears in a number of family members, it is called familial Alzheimer's disease and is thought to be caused by an altered gene. Scientists are exploring the metal aluminum as a possible toxic agent involved in the development of Alzheimer's. Also being studied is the role of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, as declining levels of this chemical result in more severe symptoms of the disease. Some scientists believe the abnormal proteins found in plaques in the brains of Alzheimer's victims may be the key to understanding the disease. Yet another factor being studied as a possible cause is a slow-acting virus.

A growing problem

The Alzheimer's Association, a nonprofit research and support organization based in Chicago, estimates that more than 100,000 Americans die of Alzheimer's each year, making it the fourth leading cause of death among adults in the United States (after heart disease, cancer, and stroke). The cost of caring for Alzheimer's patients is projected to be $80 to $90 billion per year. As more and more citizens live into their eighties and nineties, the number of Alzheimer's disease cases could reach 14 million or more before the middle of the twenty-first century.

[ See also Aging and death ; Brain ; Dementia ; Nervous system ]

My grand mother(88yrs of age) had a very bad fall approximately 20yrs ago which her health deteriorated quite rapidly,with more falls & forgetfullness.

My question to you is,

Could this fall have contributed to my grand mother having/getting Alziemers - Dementia?

I quick reply would be greatfull,

Thankyou, regards Leanne.