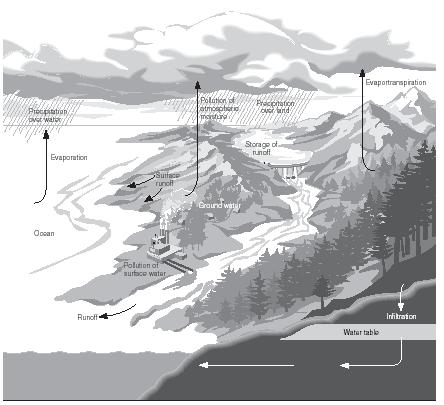

Hydrologic cycle

Hydrologic cycle is the phrase used to describe the continuous circulation of water as it falls from the atmosphere to Earth's surface in the form of precipitation, circulates over and through Earth's surface, then evaporates back to the atmosphere in the form of water vapor to begin the cycle again. The scientific field concerned with the hydrologic cycle, the physical and chemical properties of bodies of water, and the interaction between the waters and other parts of the environment is known as hydrology.

The total amount of water contained in the planet's oceans, lakes, rivers, ice caps, groundwater, and atmosphere is a fixed, global quantity. This amount is about 500 quintillion gallons (1,900 quintillion liters). Scientists believe this total amount has not changed in the last three billion years. Therefore, the hydrologic cycle is said to be constant throughout time.

Earth's water reservoirs and the water cycle

Oceans cover three-quarters of Earth's surface, but contain over 97 percent of all the water on the planet. About 2 percent of the remaining water is frozen in ice caps and glaciers. Less than 1 percent is found underground, in lakes, in rivers, in ponds, and in the atmosphere.

Solar energy causes natural evaporation of water on Earth. Of all the water that evaporates into the atmosphere as water vapor, 84 percent comes from oceans, while 16 percent comes from land. Once in the atmosphere, depending on variations in temperature, water vapor eventually condenses as rain or snow. Of this precipitation, 77 percent falls on oceans, while 23 percent falls on land.

Precipitation that falls on land can follow various paths. A portion runs off into streams and lakes, and another portion soaks into the soil, where it is available for use by plants. A third portion soaks below the root zone and continues moving slowly downward until it enters underground reservoirs of water called groundwater. Groundwater accumulates in aquifers (underground layers of sand, gravel, or spongy rock that collect water) bounded by watertight rock layers. This stored water, which may take several thousand years to accumulate, can be tapped by deep

water wells to provide freshwater. It is estimated that the groundwater is equal to 40 times the volume of all the freshwater on Earth's surface.

A plant pulls water from the surrounding soil through its roots and transports it to its stems and leaves. Solar heat on the leaves causes the plant to heat up. The plant naturally cools itself by a process called transpiration, whereby water is eliminated through pores in the leaves (called stomata) in the form of water vapor. This water vapor then moves up into the atmosphere.

Solar heat also causes the evaporation of water from ground surfaces and from lakes and rivers. The amount of evaporation from these areas is far less than that from the oceans, but the amount of evaporation is balanced as gravity forces water in rivers to flow downhill to empty into the oceans.

An inconsistent cycle

Although the hydrologic cycle is a constant phenomenon, it is not always evident in the same place year after year. If it occurred consistently in all locations, floods and droughts would not exist. However, each year some places on Earth experience more than average rainfall, while other places endure droughts.

[ See also Evaporation ; Water ]

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: